‘

TUBBY’ AND ALADDIN’S LAMPThe story of Toc-H

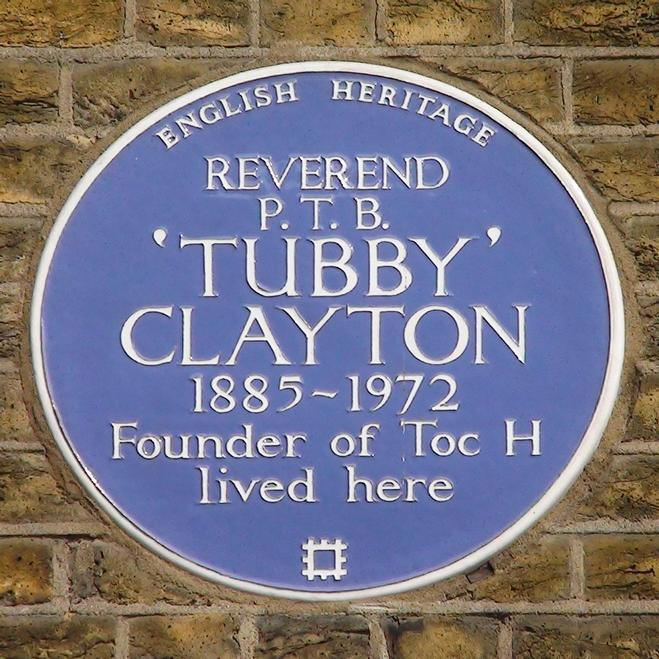

2014 has been a year for commemorating the outbreak of the ‘War To End All Wars’. There have many events across the globe and probably the one uppermost in most people’s minds has been the planting of ceramic poppies that carpeted the moat of the Tower of London. There were visits to the battle fields of Belgium and France and several members of our congregation travelled to Ypres to pay their tributes to the many that had died for freedom from tyranny. Next year there will be another centenary near Ypres, at Poperinge which is a small town situated a few miles from the trenches. During the World War 1, it was a busy transfer station where troops travelling to and from the battlefields were billeted. In 1915 an army chaplain, the Reverend Phillip (Tubby) Clayton was sent by his senior chaplain, Neville Talbot to Pops (as it was called by the soldiers) to set up a rest house for the troops.

Tubby rented a hop merchant’s house and made this his base. It was called Talbot House in memory of Gilbert Talbot (Neville’s brother who had been killed earlier in the year) and it opened on December 15th 1915. Very soon it became known as TH and later, using radio signaller’s speak, Toc-H. It was to grow into a world wide movement.

Tubby ensured the house was open to both officers and other ranks. He provided a place of peace and comfort. There was a large kitchen where copious amounts of tea were drunk and a library where books were checked out by the leaving of a cap behind in lieu of a ticket. This was very shrewd of Tubby because he knew that no soldier would go on parade without his cap, thus ensuring all his books were returned. As a former librarian that appeals to me and I wish we had had a similar scheme! Toc-H had a large walled garden where the men could sit in peace for a while away from the carnage of the front line. At the top of the house was an attic room which became the ‘Upper Room’, a chapel which was to become the focal point of the house. Throughout the war, Toc-H was an oasis of sanity for the men who passed through Pops. Here there was fellowship, entertainment and the chance to leave messages to missing comrades in the hope that they would also pass that way and see them.

At the end of the war, Tubby returned home to set up an establishment for the training of soldiers who wished to be ordained. He remembered the fellowship of Toc-H and resolved to open a new Talbot House in London. He gathered together many of the men who had passed through Talbot House during the war and the first committee was formed in November 1919. The name Talbot House was dropped and the soldiers’ nickname of Toc-H was adopted. Their first house was in Queensgate Place in Knightsbridge, as a hostel for men coming to the capital to work. Very soon they outgrew it and moved to a larger place in Queensgate Gardens called, in typical army fashion